Louisiana Museum of Modern Art- The Cold Gaze (Germany in the 1920’s)

Hej igen mine venner,

Yesterday, we experienced the first snowfall of the winter season in Copenhagen. I could tell that there were mixed emotions on the streets of the city center: excitement and dread that the winter season has finally come. I spent this Saturday taking the metro for about one hour from Norreport Station to Humlebaek Station. Here, I visited the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art as I have been recommended by many fellow students that the new exhibition was a must-see, and they were not wrong!

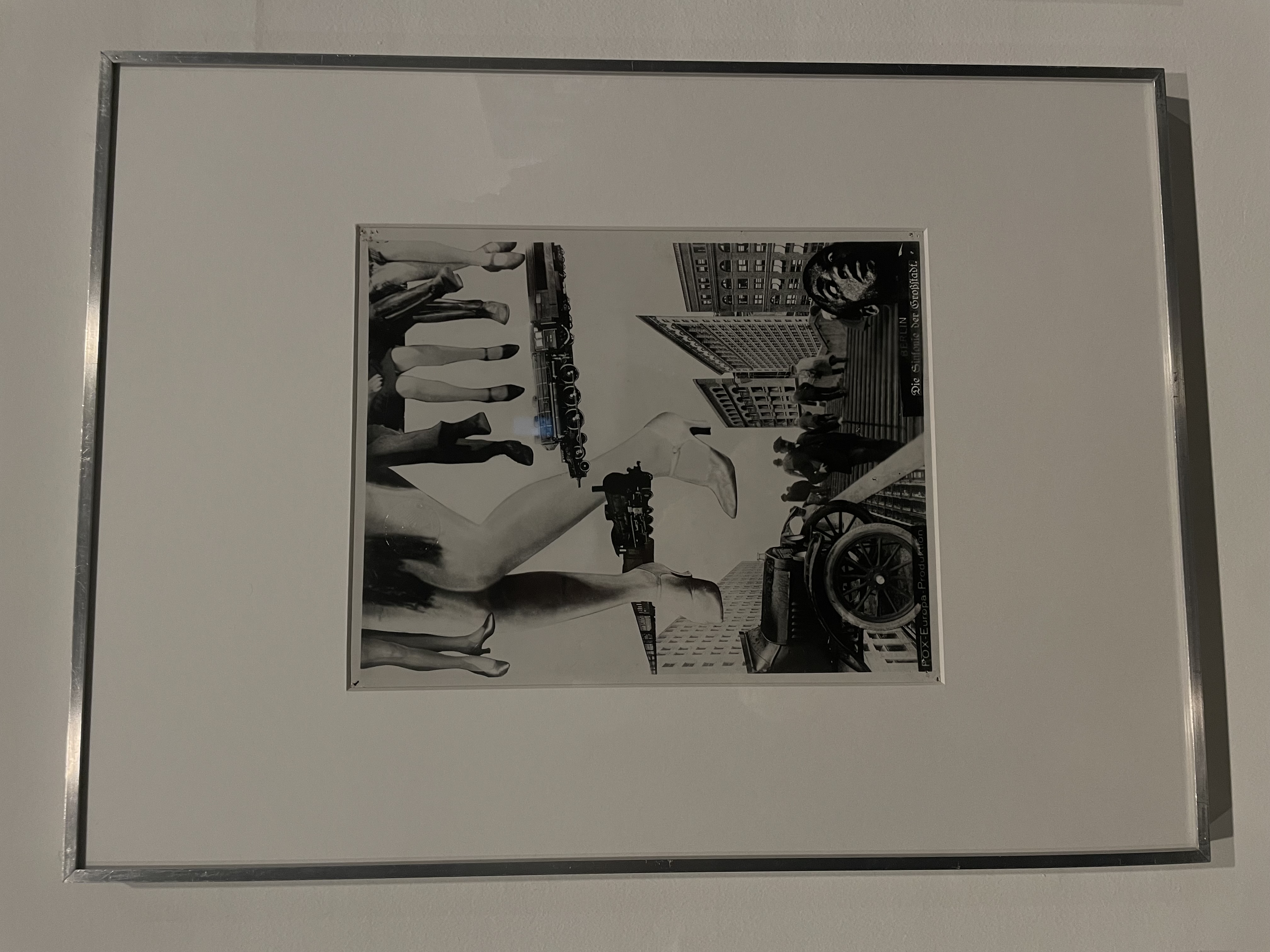

One of the new exhibitions at the museum is called The Cold Gaze. Which portrays Germany in the 1920’s as a journey a century back in time to the multifaceted art and culture of the Weimar Republic. With more than 600 works, the exhibition presents not only painting, drawing and photography, but also architecture, design, film, theater, literature and music. In the aftermath of World War 1, Germany is rocked by poverty and political unrest, while the brief flourishing of democracy during the Weimar Republic (1918-1933) is cut short by the Nazis’ rise to power. The exhibition unfolds along two tracks. One, is a thematic presentation of the striking 1920s German art movement Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). The other, showcases more than 200 photographs from the German photographer August Sander’s lifelong project Menschen des 20 Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th Century).

August Sander (1876-1964) has been named as one of the most important German portrait photographers of the 20th century. He was the son of a mining carpenter in Herdorf, Westerwald. In his youth, Sander himself worked in a local mine. Meeting a photographer aroused his interest in the photography industry, and he bought his first photographic equipment with support from his uncle. Sander’s project inspired later generations of photographers, including the American photographers: Diane Arbus (1923-1971) and Walker Evans (1903-1975). As Sander put it: “The original thought behind my photographic work People of the 20th Century, which I started in 1910 and which comprises some five or six hundred photos, of which a selection was published in 1929 under the title Face of Our Time, was nothing other than an avowal of faith in photography as a global language, and an attempt to paint a physiognomic portrait of the German people.” There is a large selection of photographs from People of the 20th Century, the life’s work of August Sander. This is a series he began working on in the mid-1920s. I felt very fortunate to be able to see these raw photographs in person showcased at the museum. This monumental image atlas is a classic in the history of European art and photography. In a society marked by violent upheaval, the movement’s artists strive to capture modern everyday living, representing the workaday life of ordinary people in a realistic, sober style often stripped of sentiment. Alternatively, some artists turn up contrast and distortion in their work, presenting a challenging set of images. The main themes in the exhibition are life in the big city, functionalist architecture, technological advances, nightlife with cabarets and nightclubs, sexual liberation, promiscuity and prostitution, alongside critical images of the tough lives of the working class and the new role of women. The exhibition is divided into seven chapters, encompassing a range of art forms as well as a wealth of historical documentation.

One of my favorite pieces of art displayed at the museum was the Big Zep. The Big Zep is a collection of 303 photographs of zeppelins, taken by anonymous people between the years 1924 and 1939. They were collected by the Berlin typographer, author and publisher Günter Karl Bose at flea markets over the last 40 years. For him, the pictures of the zeppelins represent a metaphor. They not only convey modernist euphoria, but also an expression of the German mentality in the interwar period, which sought a new ‘messiah’ represented by modern technology that would help overcome the humiliation of defeat after World War I. Big Zep is the American term of admiration for this object. As a figure of the gaze, the zeppelin embodies a new and dynamic vision – the low angle shot of the 1920s and 1930s – and at the same time an abstract object floating in the space of the image. Big Zep also constitutes a cross-section through the amateur photography of the time, a unique collection that can no longer ever be reconstructed.

Overall, the museum was an amazing last minute plan of mine. With only a month left of my journey abroad in Denmark, I am trying my best to see as much as I can with the limited time I have due to final exams approaching. If you ever find yourself in Copenhagen, I would definitely recommend taking an afternoon trip to visit the Louisiana Museum. Even if the exhibitions have changed by then, it is still an amazing museum to visit located at a small seaside village in Denmark.